latest

Fictions: All I Asked For

All I Asked For

Read the second instalment in our Fictions series.

Text by Anne Charnock, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

Read the associated “Getting Real” blog, exploring the technology, science, policy, and societal implications of the themes from the story here.

All I Asked For

Anne Charnock

Alice performs ten movements in twenty-five minutes, including two strong kicks, plus a shoulder roll and what I can only describe as a shiver. I am so proud of her. She flexes the muscles in her arms, more so than yesterday. And with her hands relaxed, her fingers curled inwards, she looks as though she’s play-boxing. I make a note—10 in 25—in her activity diary, just as the doctor ordered.

Noah turns to me and grins. “I’ve been looking forward to this all day, watching her movements, and counting,” he says. “Let’s do it again.” We always do.

This has become our routine since Alice turned twenty-eight weeks. Noah and I sit together at home twice a day and check her activity—specifically, how long it takes for her to make ten movements of any kind. We view her, at many times her actual size, on our sitting room screen. Alice in her dream state—a live feed from a camera focussed on our baby in her baby-bag, fifteen miles away in a gestation ward. Alice in a clear plastic womb of sorts, gestating in a fluid close to natural amniotic, her umbilical cord connected to a plastic tube. Her own little heart pumping the flow of blood. And an overhead monitor with flickering green and red against black, revealing her vital signs.

“She’s always more lively in the evening, isn’t she?” I say. “I reckon they feed extra nutrients to her at this time to simulate a mother’s evening meal.”

While at work today I tried to check on Alice and her activity because she seemed a little sluggish yesterday. But the office was manic. I slipped out at lunchtime to buy a sandwich and took a quick peek at her on my phone. She seemed fine and, to be honest, I’m glad I didn’t make an actual count. It’s something Noah and I enjoy doing together.

We sit side by side and watch for any movement. I place one hand on my belly, and when Alice kicks I imagine her kicking inside me. Or at least I try. I don’t tell Noah I’m imagining this because he might feel left out, or he may wonder if I’m regretting our decision.

When I look back it all seemed so rushed, and I wish now I’d insisted on waiting another week or two. I should have stood firm, because it seemed unfair to migrate the baby before I felt her first kick. My preemptive caesarean occurred at twenty-two weeks. Alice left me behind. She became free, to reach her ideal birth weight, with perfect nutrition, in the gestation ward.

Just one kick. That’s all I asked for.

“It’s so much better being able to see her,” I tell Noah in a show of solidarity. He leans towards me and kisses my forehead. His gentleness breaks me, and I wipe away tears. We met only three years ago and didn’t expect children to come our way. Our Alice. My first pregnancy. When Alice is born, I will be forty-six years old.

My doctor referred me straightaway to the hospital. An automatic referral, she said. Standard practice for a person of advanced maternal age. At the initial appointment, the consultant talked me through the elevated risks of older mothers giving birth prematurely. His tone seemed to say, Look how much you and your baby could cost us. At the second appointment, he looked at my scans and repeated his concerns. It’s difficult to argue when you are lying on your back on a gurney. He stood over me with a nurse by his side. I asked, “What about the danger in transferring the foetus? You seem to be swapping one risk for another risk.” I am sure the nurse tutted. The consultant, his hands spread, seemed too nervous to lower them onto my modest bump, as though the simple act of touching might precipitate disaster. He didn’t trust me, he didn’t trust my body to hold onto my baby. He kept on about “the appalling chronic conditions” visited upon a child born super-premature. I told the consultant that I felt perfectly healthy and preferred to take the risk, to carry the pregnancy. I remember the way his top lip curled. He said, “Do you really think that’s the correct attitude? We must do what’s best for the baby.”

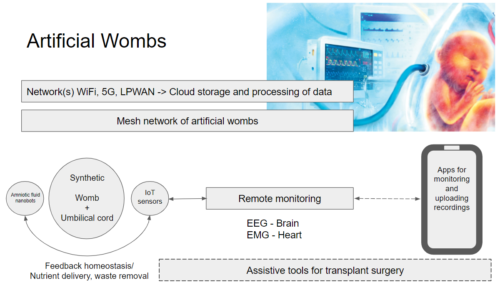

With his hands flat on my belly, he told me that one day most babies would gestate from conception in an artificial womb. “But for now—” he sighed “—we must do what we can for high-risk cases. Migration to a baby-bag is a huge step forward.”

Noah and I go to bed early because tomorrow is visiting day. Noah often likes to be little spoon. But tonight, and most nights since I became pregnant, he’s big spoon to my little one. He squeezes me tight, kisses me on my neck. “One more sleep,” he says. And we both giggle. Momentarily, I glean a premonition of a house filled with laughter when Alice arrives.

Only two months to wait. Sixty-three days to be precise. We will attend the birth—the opening of the bag. The umbilical will be cut and clamped exactly as happens with a natural delivery.

On my bedside table, I keep a small screen linked to the camera feed from the ward. I kiss my fingertips and touch the screen. “See you soon, Alice. Sleep tight and I’ll sing to you tomorrow, something new.”

Earlier in the day, I recorded myself singing a song—one I’d considered cheesy until recently. I emailed the recording to Alice’s playlist, now full of similarly cheesy songs that now completely melt me. I close my eyes. Together forever.

If I wake in the night, I will gaze at her for a few moments before slipping back to sleep.

*

We sign in, sanitise, show our parent badges to two security guards and enter the baby ward. We see Alice in the hospital only once a week, and this is our ninth visit. If I had a choice, I would come here every day, but the hospital restricts the number of parents in the baby ward at any one time. So, for six days of the week, my chest aches with the loneliness caused by our separation—a voluntary, if not totally willing, separation. During the six non-visiting days of the week, I distract myself by working extra hours and pounding the treadmill at the gym. Anything to speed from one visit to the next.

As we enter, a nurse approaches us through the semi-darkness of the ward and leads us to Alice. She’s in a different bay to her usual one, with five other foetuses rather than the usual four. A familiar anxiety breaks surface. I check the labels attached to her baby-bag.

“It’s definitely Alice,” says Noah.

“Just checking.”

He thinks I worry too much. And I know the hospital has systems and processes that everyone deems fail-safe. But, to me, it’s easy to imagine a mix-up. I don’t understand how Noah can be so trusting. After all, full-term babies look similar to one another, so these foetuses must be difficult to differentiate for the medical staff.

“We can tell it’s Alice now. Look at those ears. Just like mine, poor thing,” he says. It’s true. There’s no mistaking those ears.

I don’t tell him, but I suspect my anxiety over a mix-up has a deeper root. The way I see it, if I gave birth the normal way, I’d know for sure that the baby was mine. As soon as the baby was delivered, I’d hold her. There could be no doubt.

The nurse says, “Alice is doing so well. No problems at all. She seems very sensitive to touch this week.”

I step forward and place my fingertips against her back. Her legs make a cycling motion. I want the nurse to leave us. I don’t want anyone to speak.

“She hasn’t much room. What happens if she grows too big for the bag?” asks Noah.

“She’ll be fine,” says the nurse. “It gets pretty cramped in a real womb.”

Noah says, “We posted a new recording this morning.”

“Well, I’ll leave the three of you to enjoy it. I’m at the other end of the ward with some new arrivals. Just wave if you need me.”

I glance across and notice, at the far side of the ward, a row of baby-bags arranged close together without any separation into bays. I wonder if Alice’s move is part of some reorganisation.

Noah pulls over two chairs and we sit as close as we can to Alice. We lean forward and take an earpiece each. After a few minutes of older recordings, the new song begins. I laugh, embarrassed, when my voice fails to hit the top note. And at the same moment Alice’s limbs seem to quiver as though she’s excited.

“Look at her. She loves it,” says Noah.

We take it in turns to place a palm on the bag, close to Alice’s body. And as Noah removes his palm, Alice appears to swim. I reach out, touch the bag and feel her elbow press against the ball of my thumb. My voice misses the top note again.

Yes, better days lie ahead. This is the sweetest moment, and I bend down so that my face is an inch away from Alice.

*

“Better say our goodbyes soon,” says Noah. “Visiting time is nearly over.” On cue, the nurse appears. “Not rushing you, but another parent is due to visit this bay in ten minutes,” she says.

We overlapped with another parent last time, and I felt uncomfortable sharing the space. I always feel self-conscious when other parents are around even though we’re all in the same boat. It’s obvious that I’m an older mother, and so it’s clear that I had little choice. But the young mother I met last time seemed eager to tell me she had no choice either—cancer treatment. Questions otherwise hang in the air, and I’m sure we’re all aware of them. Is your baby-bag strictly necessary? Did you fake a phobia about childbirth? Did you want a baby-bag to protect your career?

“Are you reorganising the ward?” I ask the nurse. “I’m wondering why Alice has been moved. And I see there’s a row of baby-bags, which you haven’t grouped into bays.”

“Just temporary. A bit of overspill from the ward next door. That’s the ward that doesn’t receive visitors.”

She raises her eyebrows, and I know she’s referring to terminations, and foetuses rescued from chaotic homes.

“That’s a shame,” I say. “Not having visitors. Is their world silent? No voices to listen to.”

The nurse leaned into me. “Unofficially, the nursing staff read stories to them and sing songs. We make the recordings on our own time. No one asks us to do it, but it only seems fair, doesn’t it?”

I find myself suddenly welling up. “We could share our recordings, couldn’t we, Noah?”

He stares at me. Without answering.

“Jeez, that came out of nowhere,” says Noah as we leave the hospital. “I didn’t know what to say.”

“Sorry. It just came out. I felt sorry for them. I mean, why should Alice have songs and stories, while they only hear the sounds of the ward—trolleys clunking, the nurses chatting to one another. Those foetuses don’t know they’re any different.”

We slip into silence for the journey home. We love our visits to see Alice, but it’s a deep dread feeling to leave her behind. An abandonment.

My own mum says I don’t know how lucky I am. She only had me. A difficult birth. She claims I’d have a dozen brothers and sisters if baby-bags had been invented sooner. Slight exaggeration, I know. But if Mum has told me once, she has told me twenty times that childbirth can’t go on. She mentions the Stone Age. She barely listens to me.

*

Noah places my dinner on the table. He takes care of me even though I’m not pregnant, as though my burden has simply shifted from a physical dimension. I carry brittleness rather than weight.

“I keep thinking about the other foetuses. The other babies,” I say.

“I’m sure they’ll end up in good homes. Listen, let’s do another count before bedtime. I think Alice is really responding to your new song.”

I pick at my meal. I’m off my food. No one will ever say to me, You’re eating for two now.

*

Ten movements in twenty-three minutes. I make a note. Another record breaker.

Noah says, “When she is here, we’ll forget all this. Alice will be born at full term, and she’ll look forward to a long, healthy life. We owe her that.”

I want this to be true. But I fear I’ll never lose that feeling of dread when we leave our baby with the nurses, strangers really. And I still believe we could have waited. I deserved to feel Alice kick. But clearly, it’s not about me.