latest

Fictions: Stealthcare

Stealthcare

Read the eleventh instalment in our Fictions series.

Text by Liz Williams, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

Read the associated “Getting Real” blog, exploring the technology, science, policy, and societal implications of the themes from the story here.

Stealthcare

Liz Williams

I was taken to the ship on a private jetboat. The pilot smiled as she assisted me on board.

“Good evening. Enrico Calalang? How nice to welcome you to Global Line. Was everything acceptable with regard to your hotel?”

“Most acceptable, thank you.” I tried to convey the impression, which I’m sure was a failure, that as an insurance investigator, even a senior one, I was accustomed to staying in top establishments.

She bobbed her head. “I do hope the Princess Charlotte will also meet your expectations.”

“I’m sure it will.”

Over the years in which I’ve been involved in this industry, I have learned to discern the sound of wealth, and that sound is silence. The London Hilton Ten had been a hushed place. Since then I had been entirely insulated from the chaos of the city, from a peaceful night enveloped in maximum thread sheets, to the breakfast served to me by a smiling, unspeaking waitress. As though I, lost in my own banal thoughts, was too important to be bothered with the inconsequential chatter of lesser mortals. I suppose this is what it is like to be rich.

But I glimpsed parts of this ancient city that were less luxurious. Since the advent of stealthcare bills, as they’re not-so-humorously called, the Brits are rueing the day that they let the old NHS slip through their fingers. Last night, I’d overheard the hotel manager warning a new member of staff to take care not to let any of the med beggars into the garden compound (“they’ll only annoy our guests – I won’t put up with it, I tell you. Call the police if you see any”).

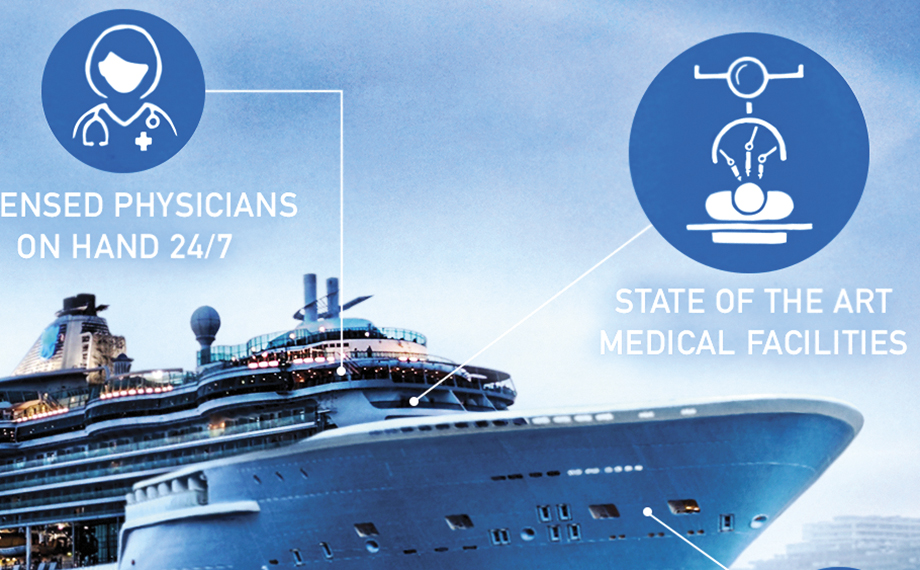

And now the Princess Charlotte was looming further down the Thames as the jetboat shot along the river. She was quite a small ship in comparison to some of the retirement vessels which circle the globe – floating palaces of luxury, filled with the wealthy, the elderly, and the ill.

“Nearly there,” the pilot said unnecessarily, over her shoulder.

Once on board, I was whisked by a soft-voiced steward to my quarters. This would be my home for the next 24 hours, a complimentary cabin offered by Global Line. I had discussed this back at the office and we were not sure whether this was actually a bribe or not, but in the end we decided that we had few enough perks and I might as well accept it, as long as I declared everything properly on my expenses form.

Once installed, I was served a fruit juice cocktail which I was unable to identify until I read the lengthy description which had been sent automatically to my phone. The ship’s system had logged into my wristband, detected some minor vitamin deficiencies (probably caused by a few long flights and too little sleep) and the cocktail was intended to supplement the lack.

I sat down by the porthole in a comfortable chair, sipping my drink, and brought up the case file on my pad. I was familiar with the details but flicked slowly through the case notes once more.

Rosalind Lee. Age 74, born in Edinburgh, educated in Hong Kong, where she had spent much of her life. She was the wealthy widow of an Anglo-Taiwanese pharmaceutical CEO: a former scientist who had set up Buena Vista, one of the best known of the current set of global wellness brands. She had applied for residence on the Princess Charlotte three years previously, following the death of her husband, and had lived on the vessel ever since. Her application had been approved by my insurance company, according to the usual criteria: primary among these was a pre-existing condition clause. I had read this many times but now I read it again. As was usual, it was customised: setting a higher premium on some conditions which are relatively easily treated, such as various forms of cancer, but it did clearly stipulate that some conditions would not be permitted under this policy. One of these was WIS – Wehlberg’s Inflammatory Syndrome. Mrs Lee had tested negative for all the early markers – not just in her annual medical checks, but also from the hourly readouts from her wristband over the course of her life – yet now she was positive for WIS.

According to our medical staff, that wasn’t possible. Either she didn’t have WIS, or her earlier wristband readings had been wrong. But once they’d pinpointed the illness – one of the several underlying conditions that have turned out to be responsible for a lot of auto-immune diseases – the markers were actually clear, I understood.

“Discovery of Wehlberg’s was a game changer,” Dr Pramasan, one of my medical colleagues, informed me. “You know about it, yes?”

I’d nodded. I remembered when it had been discovered, tying together all those vague symptoms from things like fibromyalgia to IBS, which a lot of doctors had refused to accept even existed, decades ago.

There’s no known way to falsify the readings on a wristband – so many hackers have tried, but they’re always found out. So we were presented with a quandary: had Mrs Lee committed an impossible fraud, did she have an impossible medical history, or was it some bizarre mistake? My company could have run the data through an AI, but the human touch is still valued – more to make the clients feel comfortable than anything else.

I was to interview Mrs Lee later and get my own impressions of her. I was certain, though, that I had not made a mistake and neither had the medics who had studied it before me. Dr Pramasan had been clear.

“There’s nothing on the readouts for over twenty years to indicate any issues. She’s been quite healthy, apart from an early indication of diabetes which obviously they were able to cure, and a couple of major viruses. But there are none of the markers for WIS.”

“And her readings would have picked it up?”

“Absolutely. Wristbands were brought in after they discovered WIS and all its cohort conditions and because it has been the cause of so many A-IDs, the WHO poured billions into getting it linked in.”

I perused the reports again, wondering if I’d missed something. This attention to detail is part of what drew me to this work in the first place, but with it comes a simmering underlying anxiety which – well, that appears on my readouts, too, and if I didn’t take compulsory medication for it, then I wouldn’t be in my job for much longer.

I didn’t think I’d missed anything. Time to interview Mrs Lee.

She was waiting for me in her cabin, along with a fluffy white dog. I asked her to authorise a temporary sharing agreement and she did so without demur. To put her at her ease, I joked about sharing the dog’s readouts, too: his band was in his collar. She laughed and my phone pinged in to let me know that the agreement had been verified and via my retinal implant I could now see her readouts scrolling down the air to my left. Elevated levels of adrenalin: she was nervous. But some people feel guilty if they even see a policeman. I could see the WIS markers, slightly lowered levels of calcium, blood pressure also rather high but she was medicated for that. She’d had no alcohol recently, but some caffeine. The cup of cooling tea in front of her could have told me that, though.

“I wasn’t really sure what this was about,” Mrs Lee said. “I’ve always paid my premiums on time, and I’ve only ever made one claim before now. Is there a problem with my insurance?”

I sighed. “I’m afraid there is. We have a – a discrepancy. You see, you’ve recently been diagnosed with Wehlberg’s, haven’t you?”

“Yes, that’s correct. I thought my insurance would cover it. Is that not the case?” Her hands played, agitated, in her lap.

“Well, usually it would, but the trouble is that WIS has to be a pre-existing condition, by definition, and your insurance cover explicitly rules that out. You’d need to have taken out a separate plug-in clause for WIS and cohort illnesses.”

“I can assure you it isn’t pre-existing.” She sounded distressed, but quite definite. “I’ve never shown any signs of it before.”

“The doctors say that this is unlikely, I’m afraid. In fact, you’d be a medical miracle. Look, Mrs Lee, no-one is accusing you of any kind of wrongdoing. There’s clearly been some kind of error, and we just need to pinpoint where it is.”

“But if you’re not going to cover it, I can’t get treatment, is that it? Or I can, but I’ll have to pay for it. I gather it could be extremely expensive.”

I had the impression that she was genuinely worried. But why? Because she’d somehow managed to initiate a major insurance fraud, or because there actually had been some kind of mistake? She seemed quite genuine, but I’d only just met her. Yet readouts will show indicators when people are lying: it’s not an absolutely precise science yet, but it’s pretty reliable. And there were no such indicators here.

“I’m sure this is just an error and we can sort it out. You might be able to get a covering clause for it, anyway – we might be able to get it written into the policy.” At a much higher premium. And only if she hadn’t made a fraudulent claim.

“My husband lost a lot of money before he died, in the crash. He’d already sold his shares in Buena Vista but – well, to be honest, he wasn’t happy about that. He felt the board had pushed him out and he was very bitter – I feel it contributed to his final illness. I know this ship looks luxurious, but it’s actually cheaper than living on land for me.” She paused. “It’s a tax thing, you see. It’s the last thing he did for me.”

I nodded. Living aboard a luxury cruise ship had sounded expensive to me when I first came across the idea, and the sums involved still weren’t low – apartment cabins here cost several million – but there were multiple advantages. Including the large onboard hospital. If Mrs Lee had to fund her own treatment, it would be questionable whether it would be cheaper to do so on board or off: she would still need to pay, either way.

“Tell me about your husband,” I said, and she needed little encouragement.

“Oh, he was a wonderful man…”

The late Mr Lee had been many things, I reflected as she spoke, but ‘controlling’ would have been the word that most readily came to my mind. When she had finished her account, I said, “It sounds like a long and marvellous relationship, Mrs Lee. Now, let’s talk about your wristband. Nothing’s ever gone wrong with it?”

“No, it’s the only one I’ve ever had.” She glanced at it with the rueful affection that we often devote to our lifetime wearables. “It’s been with me for years, since I was first fitted with it. My husband’s company were at the vanguard of bringing them out.”

Perhaps I should not have felt sorry for her and yet, I did. I believed her, but I still had a medical mystery to solve. At this point, a steward came to the door with a query of some sort and they went into the corridor, leaving me alone to study my surroundings.

At the moment, I had an excellent view of Tower Bridge and the London skyline. But it was the photos on the walls that attracted my attention: hologrammatic images of Mrs Lee and family projected within ornate frames. There was a formal posed portrait at the centre, of a younger version of herself and a man whom I recognised from her files as her husband. Mrs Lee’s wristband was clearly visible. When I had seen it that morning, its subtle aqua tones had matched her smart blue suit, but in the portrait, it was a soft pink. The holographic image was quite large, but obviously it could be made larger… I took out my phone and, with care, took an image of Mrs Lee’s wrist, from several angles, moving around the image to get as full a picture of it as possible.

Then I heard her coming back, so I sat down again and sipped my excellent coffee.

“…should be fixed now, but do let us know if you have any further trouble…”

“Of course. Thank you so much.”

I checked when Mrs Lee been issued with her wristband. As an older woman, she had not had one as a child, but had been fitted in adulthood. All this was clearly shown on her medical records but I listened to her reminiscences anyway.

Back in my own berth, I wrote up my report and sent it in. Then I sent the images from the old hologram to a colleague in the imaging lab: if anyone could tell me the story of Mrs Lee’s bracelet, it would be Gilberto. Shortly after this, my phone pinged and I saw that he had responded: Will get right on it. What are you looking for?

I messaged back: I don’t know. Will a hologram show the QR and the rest of the codes?

Yes, it should do.

The symbols are too small for someone to see with the naked eye, though they’re all over your medical records anyway. But Gilberto could play around with those images in all sorts of ways.

After this I did some more paperwork and in due course was brought a nutritionally balanced, expertly prepared dinner. I still had not heard from Gilberto, so after dinner I poured myself a small Scotch from the berth’s mini bar, ignored the warning ping of my wristband informing me that I was about to imbibe a harmful substance, and watched the news. My Scotch would show on my readouts, but would not contribute to the points for a healthcare reprimand. And then I slept, the mattress configuring itself to an optimal shape for my slight lumbar problem and the room misting itself with a soothing combination of lavender and chamomile to minimise my chances of insomnia.

In the morning there was still nothing from Gilberto. As I was finishing my croissant and contemplating more coffee, my phone finally pinged.

“Well,” Gilberto said. “This one’s been interesting! The QR and the other recog symbols are the same. But the band isn’t.”

“What?”

“I went for a full spectrographic analysis and I think the wristband in the photo is an earlier model. Made by Buena Vista, like the one she’s got now, and very similar, but not the same.”

“But there’s no indication that she had an upgrade and that would be clear from her readouts.” If you upgrade your device, it can only be done in a hospital that’s cliented to the wristband provider and you’re monitored the whole time, I reflected. It’s not like changing your phone. And not even that common: it’s not you who decides, but your provider, and most people keep their wristbands for the whole of their lives, as Rosalind Lee said she had done. Any software updates are done automatically.

“Of course it would. She didn’t say anything to you about changing it?”

“No, on the contrary. She said she’d always had this one.”

“But she hasn’t.”

“So we’re dealing with fraud, then.”

“The thing is, Enrico, it’s so hard to do with these devices. You know that – they have to be as foolproof as possible because the stakes are so high. They’re incredibly difficult to hack, all the data goes straight to the Cloudscape, and you obviously can’t just take them off.”

We talked for a while further and Gilberto promised me that he’d stay on the case.

I had a number of options.

Mrs Lee’s wristband was the same one and the imaging results were wrong.

Or she had some kind of sudden onset WIS, previously unknown to medical science.

Or she was lying and had perpetrated a fraud in order to claim for treatment which was ruled out by her insurance.

Or someone had done it for her and she didn’t know. I wondered again about the late Mr Lee. If anyone was capable of hacking the system, it would be a scientist who led one of the companies who produced wristbands. Had he seen her readouts, noted the early signs of WIS and swapped her band? Surely, though, it would be easier simply to have changed her insurance and bought a higher premium with a clause that covered WIS? Of course it would. Even if he’d lost money in the crash he’d still been wealthy enough to buy his wife a permanent cabin on a retirement cruiser and our premiums aren’t that high.

The only thing I could think of was that he had found a way to buck the system – perhaps his reasons were not even financial, I speculated wildly. A final gift, to release his wife from the system that he himself had helped to create? A final small revenge, by a controlling man against the corporation who had forced him out? Or a Trojan Horse to betray the woman who had thought him so marvellous a husband? Or was this common practice among the wealthy and we just didn’t know?

I was obliged to report Gilberto’s findings to my manager, and flew back home the next day. There were meetings to which I was not privy. I waited for several weeks, wondering whether Rosalind Lee would be charged, but nothing seemed to happen and after a while, I realised that I would never know for certain what had taken place. I made some discreet enquiries and found that Mrs Lee was still living on the Princess Charlotte, now cruising the Mediterranean. My own feeling is that her husband had replaced her wristband, but without her knowledge, for reasons unknown and that her bewilderment during her interview with me had been genuine. And I suspect that it was simply too embarrassing for both Buena Vista and my employers to face a scandal and to put the knowledge out there that medical records could be falsified. Especially if, as I had surmised, this was not unknown among the wealthy and powerful and they couldn’t risk that piece of information getting out.

Six months later, just for the hell of it, I entered a company raffle. The top prize was a retirement berth, for two, on one of the ships owned by Global Line. My luck must have been in. It is on the Princess Louise, a sister ship to the Charlotte. My wife and I will be flying out next week, to inspect our new floating home. My wristband readouts show that I am very excited.