latest

Fictions: CareFree

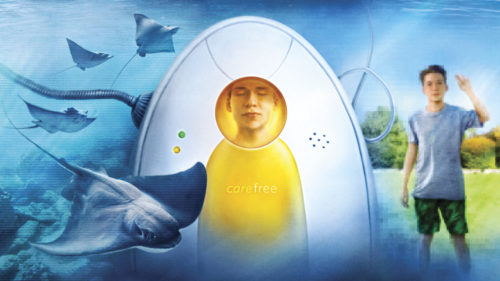

CareFree

Read the tenth instalment in our Fictions series.

Text by Keith Brooke, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

Read the associated “Getting Real” blog, exploring the technology, science, policy, and societal implications of the themes from the story here.

CareFree

Keith Brooke

The house is just as I remember it, a Victorian mid-terrace with a tiny front garden laid to slabs and a front door that I know opens directly into the living room.

I pause a moment too long; my sister is expecting me and she opens the door before I manage to knock.

“Hey, Julia.”

“Steve.” Guarded, wary, her eyes flitting beyond me, checking the street. Julia’s never been comfortable with people and the wider world; always happier when that door is closed.

She’s skinny, her hair bottle-red, a little make-up around her eyes so that I know she’s made an effort. She looks much older than mid-thirties, but still better than last time I was here. Has it really been three years?

She steps back, lets me in, shuts the door with a heavy thud.

“Seen Mum recently?”

She shakes her head. Julia isn’t one for going out much.

“She sends her love to you and Billy,” I tell her.

“Tea?”

We move through to the small kitchen in the middle of the house in what used to be the dining room. With most of these terraced houses, the kitchen is in a narrow extension at the back, but that had been adapted for Billy years ago when he grew too big for Julia to get up the stairs.

While Julia fusses with kettle and cups, I take the place in. It really hasn’t changed at all: the jaded decoration, the sense of ordered clutter. Julia asks about my travels and I give her the potted summary – Venezuela, Guyana and Suriname, then Guatemala and Cuba this time – and I try not to read the same judgement I see in my mother whenever we meet, the contrast between the peripatetic life I lead and my sister’s existence, anchored in the reality of an adult son with multiple needs.

“You seem… better,” I say, as we return to the front room with our drinks. Better… calmer, happier even.

Julia shrugs.

“Billy doing okay?”

Another shrug.

“You need any help?” Money, I mean. Nothing practical. Again, I feel guilty that I never stick around and do more these days.

A shrug, and this time a glimpse of a smile, perhaps because she realises she’s shrugging in response to everything I say. “It’s okay, Stevie.” She hasn’t called me that for years. “We’re doing okay, really. You don’t need to feel responsible – whatever Mum dodges saying.” Because our mother never says out loud what she can skirt around and imply with loaded subtexts. “We’ve got a new care package now,” Julia goes on. “It makes things a lot easier.”

I don’t press her on that; I’m just happy to hear that things seem to be on more of an even keel these days. Julia and Billy haven’t had it easy.

“Can I see him?”

Julia is instantly evasive, and then I finally twig. When she talks of a new care package, she doesn’t mean they have people coming here to the house to look after Billy. She’s moved him into a home. That must have been a hell of a decision for her. I tried unsuccessfully to persuade her of it last time I was here. Billy was sixteen by then, and must have weighed as much as two Julias.

Again, I choose not to press. The details will emerge, and I can visit Billy in his new place. Talk to him like I used to, when we’d sit for hours and put the world to rights.

The relief is evident in Julia, though, now that the tough choice has been made. She still, quite clearly, lives an existence shut off from the world, but I can see that the weight has been lifted from her shoulders.

We talk some more, Julia hungry for my tales of the wider world, and I wish I’d visited sooner. I’ve been back six weeks, and have been putting this off.

When Julia goes upstairs to the bathroom, I take our cups to the kitchen and fill the kettle. The door to the extension is shut, and I wonder what she’s done with Billy’s old room. Nothing, I suspect; she wouldn’t want people in the house to decorate or whatever.

Recalling those long talks we used to have, I go to the door, wrap my fingers around the cold handle, and finally open it.

Inside, Billy’s bed has been replaced by what looks like a plastic coffin with curved contours. A pod, with a clear panel on the lid, and pipes and thick plastic-tied cables snaking out from either end.

It takes a few seconds for my eyes to adjust to the gloom, and just as long for me to convince myself that what I’d seen at first glance is true, that my nephew Billy is lying there, apparently comatose, within that pod.

*

Julie has entered the kitchen, but doesn’t approach. I look back at her, then at Billy again.

“It’s not what it looks like,” she says.

And that’s when I realise: it’s not what it looks like – it’s worse. My initial assumption was that my nephew’s condition had taken a bad turn. I know his lifespan is going to be shorter than most, as the muscles deteriorate, the chambers of the heart weaken and balloon, the lungs start to fail. But Billy’s condition hasn’t worsened; this is a choice Julia has made for his care, the “new care package” she has arranged for him. I’ve seen stories about this kind of thing, but it’s always in Taiwan or Korea; seeing it here, tucked away in an English Victorian terrace is surreal, to say the least.

Julia puts her hand over mine, still on the handle, and as she draws the door shut I back out of the room.

“It’s all automated,” she tells me. “The pod monitors Billy twenty-four-seven. Billy is fitter and healthier than ever. He might live to fifty or sixty years old. Without it, with DMD as advanced as he has, he’d be lucky to see thirty.”

“Automated? Is that how they keep the costs down?” I know how it works: private companies buy out care contracts from local authorities and offer equivalent care for the same price, making their profit in the margins. “Is Billy-in-a-pod cheaper to run than before?”

I regret the words the instant I say them, and even though she tries not to react, I see the flash of anger on my sister’s features. “We can’t all afford to…”

Gad off around the world, avoiding my responsibilities. In that instant, Julia looks and sounds like our mother.

She softens, then. “It really isn’t as bad as it looks,” she says. “You should try to see it from our side. You can visit any time, you know.”

*

I stay in a guesthouse by the river, just outside the city centre, and go online to investigate a bit more, using the contacts I’ve built up over the years as a wandering journo. Billy is on the CareFree system – Putting the freedom back into care! as the strapline says. The website and social media presences for the firm talk of personally tuned microhabitats and life system optimisation, with countless benefits for both carer and caree. Nowhere do they use the phrase life-support system, although all the tubes and wires most closely resemble that to me, bringing back painful memories of Skype and Zoom calls with our parents in Dad’s final days in intensive care.

Billy’s extra decade or two of life come at the price of putting him on mass-produced, economies of scale life support. Not comatose, as I had supposed, but fed a constant randomised stream of ersatz “memories” and “experiences”, constructing a virtual life for him. According to the spiel, Billy will have a richer experience of life through these virtual streams than he would ever have had living in the back room of his mother’s Victorian terrace.

According to some of my other sources, though, it isn’t so much a rich stream of experiences as the bare minimum of crude stimuli required to prompt the brain to produce the endorphins and serotonin and other neurotransmitters that would be released if Billy was really experiencing the sun, the fresh air, the sound of the sea. Enough to trick the body into staying healthy, and living longer – whatever that “living” might actually entail.

I’ve tried hard to be objective. To understand and identify the real benefits, although the main benefit seems to be that this is an economic and effective way to manage institutionalised care’s drain on the economy. I’ve done my best to accept Julia’s choice.

But I can’t.

I’ve watched reports about the horribly limited existence of someone put in a pod. I’ve read the accounts of people who have escaped this new care regime. I’ve seen images, too, of so-called care homes in North Korea, the lifepods stacked high in warehouses of the infirm. At least that’s not happening here, and Billy remains in his own home, but still…

You should try to see it from our side. You can visit any time, you know.

*

“Billy? How are you doing?”

It’s easier if I close my eyes, try to shut out some of the virtual-reality overlays. Just concentrate on his voice.

Eyes open, and the sky is too blue, the grass too uniformly green, the trees indistinct and lacking any texture. It is a visualisation of what I had dreaded: fake imagery that does the bare minimum to fool the senses into responding in the right ways. A fake world they haven’t even bothered to render.

“Uncle Steve! Mum messaged me to say you’d come. She doesn’t like to visit herself, it’s too outdoors for her.”

I smile, and wonder if Billy can see some kind of approximation of that smile rendered in his stream. Hearing Billy is more of a shock than anything: well-formed words, no hesitation, no drawing out of every syllable as he physically drags the words out of himself. But still Billy, after a fashion.

“Don’t worry, Billy. I’m going to get you out of here. Out of this.” Does he see my gesture? The sweep of the hand that indicates his ersatz reality?

There’s a long silence before Billy finally says, “Out? How…?”

Is that desperation in his tone? A prisoner suddenly glimpsing an escape he has never imagined possible? The sheer fakery of this virtual reality masks all the normal cues, but I know Billy. I recall that connection we had, the long talks, the bond.

“Out?”

I want to reach over and take hold of his hand.

“But why?”

I open my eyes, stare at the pixelated approximation of a human form that my brain won’t accept is my nephew.

“Why?” I ask, struggling to catch up. “Because… this.” That sweeping gesture of the hand again. “A crude simulated virtual reality that looks as if it was built by a 1980s video game designer.”

“I have a life. Memories. Experiences.”

“Mass-produced, the same superficial pap that’s fed to everyone in here.” I’d sampled some of the streams, the virtual-reality equivalent of the trashiest daytime TV, a torrent of superficial imagery, compiled from the cheapest sources possible. “They keep you ticking over, Billy. You have no life here.”

“And you do out there?”

I fall silent, still unaccustomed to this articulate version of my nephew.

“You sit for hours on end watching formulaic TV and movies. You play your VR games. You do the same banal things on repeat in what you call normal life. And when you actually meet a real person, what do you talk about? The stuff you’ve watched and played. Why are my memories of experiences unexperienced any less valid than yours or Mum’s? Your reality is just as fake as mine.”

How to argue with that? Those aren’t Billy’s words, of course. I’ve seen versions of these arguments already. Billy is just parroting what he’s heard, spouting the CareFree company line.

But what if there’s a truth in there?

“I don’t live like that,” I counter. “I don’t watch endless TV. I don’t play VR games. I’ve seen the world. I’ve lived life.”

“You’re the exception, Uncle Steve, not the rule. Tell me my existence is any less rich than Mum’s. Or any less rich than the life I used to lead. Go on. Tell me.”

I can’t. I think of Julia, scared to go out into the world, scared to meet people, because her experience of people is that they have nearly always let her down. I think of Billy when I visited him last, his entire world consisting of the downstairs floorplan of that Victorian terrace: front room, kitchen, Billy’s room, and the cramped wet room beyond.

“There’s an alternative, Uncle Steve.” Billy’s words take a moment to sink through my self-absorbed reflection.

“An alternative?”

“We all know this is a cut-price reality,” Billy went on. “But there are modules, building blocks, communication channels. There’s a community. Ways to build our own richness in.”

“How do you mean?”

“I have friends here who are linking up with other realities.”

“Other realities? You mean the real world?”

“Your world, not mine. Streaming it in for us to share. You could do that, too, Uncle Steve. And maybe you could persuade Mum to give it a go.”

*

A month later I’m in New South Wales, a hundred klicks down the coast from Sydney where a succession of wide bays notches the coast, vast expanses of Bush coming down to meet a strip of golden sand. Out in the bay, a school of bull rays mosaics the surface.

We’ve been swimming with the rays, face down in the clear water. Another world. Another reality.

Me, Billy. Even Julia, overcoming her fear of outside because it’s not really outside at all, but about as inside as you can go.

I’m streaming through bodycam, motion sensors, tactile pads, body monitors. Sharing my world. Feeding Billy and Julia my experiences and responses.

And I tell myself that this is good, that we three are sharing things we would never otherwise have shared. That Billy and Julia’s now-disparate worlds are richer than they would ever, otherwise, have been. And not that I am a part of the process that is leading my species into a future where it’s more efficient to disengage entirely from the world, and each other.

“Just imagine,” a voice says in my head, and I realise I don’t even know if it is Billy or Julia speaking. “With all this… living like this… we might never have to meet again.”

It’s easier if I close my eyes, and focus only on the voice, but even then I find that I am losing track, losing touch, losing connection.