latest

Fictions: George

George

Read the eighth instalment in our Fictions series.

Text by Stephen Palmer, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

Read the associated “Getting Real” blog, exploring the technology, science, policy, and societal implications of the themes from the story here.

George

Stephen Palmer

Mel’s appointment with her new doctor was at midday. The pain was worse, centred on a tender spot lying over her uterus, and she consoled herself by deciding that getting a private GP was always going to be better than relying on the Jackson Hospital. How could it be worse? What remained of the NHS was in chaos and already one government had fallen because of the mess.

The private hospital was set in leafy grounds on the edge of town. Its waiting room was quiet, Radio 2 playing in the background, with a large area for children; plenty of toys. She was one of three patients, all women, the others each with a child. The receptionist was polite and relaxed. The whole place felt calm. In contrast, her memory of Jackson Hospital was of an untidy waiting area, posters dog-eared on the noticeboard, the remains of floor cleaning machines left to rot in corners.

She was with Dr Lee. Apparently he was experienced, knowledgeable and well thought of.

His consulting room was large, with a huge window, in front of which he sat. Yet, seeing him, she felt a twinge of concern. He looked at least seventy and he was busy at his computer.

“Please sit,” he said to his monitor. “I shan’t be a moment. We have nine minutes yet.” At last he turned to smile at her. “Miss…” He glanced away. “Cope. Very nice to meet you, and welcome to the practice. Now, what would you like to talk with me about?”

Mel had rehearsed this moment for days. “I suspect it’s a gynaecological thing,” she began.

“Well, tell me your current symptoms, and I will decide. Do feel free to speak of everything at this stage.”

She nodded, wondering why he needed to tell her that he would decide. Perhaps it was the whole Google doctor issue – people seeing their GP thinking they already knew what their diagnosis would be. She hesitated. Her problems had continued for a long time, and, inevitably, she had turned to online resources.

In a quiet voice she said, “I don’t need you to discuss prior diagnoses. The pain is centred just above my uterus, you see.”

He nodded. “Your womb.”

“Uh… yes. I’ve been bleeding constantly for over twelve months. At the Jackson I had internals, ultrasounds and a blood test. I’d take the pill, but none of them agree with me.”

“Does the bleeding stop when you take the pill?”

“Yes.”

“I have had a look over your NHS records,” he said. “There has been some bleeding from the cervix apparently, but of course that is normal for some women.”

“Normal?”

“Yes. You are twenty-four. A bit of blood from the cervix is not unusual at your age, and, if that is what is happening, then in time it should cease.”

“In time?” she said.

“Do you suffer from IBS?”

“Uh… no. I don’t think so. Why?”

“You don’t think so?”

She shook her head. One of the doctors at the Jackson Hospital had been convinced she had IBS. “What are the symptoms?”

He looked at his monitor for a while. “I suspect this whole issue is just the way your body has been put together. Women’s physiology varies enormously, much more than men’s.”

Mel sat back, reminded of her last GP. “Well, what did you think of my family history?”

He frowned. “I don’t know what you mean.”

“My aunt had cervical cancer. My other aunt was infertile. And my Mum’s periods, they were very heavy–”

“Family history is not relevant in cases like these, Miss Cope. I have not read it. My job is to assess you here and now, then do my best for you.”

“Assess already?” she asked.

“Are you at your usual weight right now?”

At once she froze. “Why?”

“People often look for a single explanation, but I suspect your symptoms are caused by several factors, one being the weight you are carrying. Dizziness, tiredness, listlessness… those kinds of things. Iron deficiency also.”

“Are you going to examine me?”

“Later, I expect. This is an exploratory session.” He smiled. “You’re an otherwise healthy young woman. I’m pretty sure that once you’ve started having babies everything will sort itself out.”

The pain is most likely to be IBS,” he continued. “But I can prescribe Tranexamic Acid for you if you like.”

“But that didn’t work before.”

“It is always worth trying again.”

Mel walked out of the room. She felt crushed.

*

Work was busy. Too busy. She felt overwhelmed, unable to concentrate, Dr Lee’s words – so softly spoken, and with a smile – echoing around her mind. Were all doctors like this? Were women so complex they could not be understood and helped by any health sector?

Her colleagues in Data Gathering at Goode Ltd were mostly male. A couple of female colleagues sympathised, but both had young families having conceived without delay. They were slim and successful. Only Roy, the geek of the department, had any time for her, and he knew little about real life.

What rankled was how her assumption of the superior nature of private practice had been falsified. With the NHS in confusion, thousands of people were taking out insurance and going private – the papers were full of the exodus. She had believed the hype. Shocked, she found herself back at work in exactly the same situation, and still in pain.

Even the private corporate status of her employer annoyed her now. Instead of aiding and complementing the NHS, she saw them as exploiting it. Private drugs, private equipment, private care. It was all wrong.

Roy put a cup of coffee on her desk and knelt down at her side. “You look tired.”

She glared at him. “Dizziness, tiredness, listlessness… must be iron deficiency then.”

He stood up, silent, his expression disappointed.

“Oh, I’m sorry Roy,” she said, glancing down at the coffee. “Rotten day.”

“Was it bad news at the doc’s yesterday?”

She looked up at him, knowing he could not understand. “It was no news,” she replied.

He nodded. “Anything I can do to help?”

His expression was so dejected she took him seriously. Was it possible he felt something for her? Most unlikely. Why would he? But then she considered what part of Goode Ltd they worked for.

“Roy… you know George?” she said.

He nodded.

“Will it be ready soon?”

“He’s ready now, but we’re finalising algorithm tests.”

“Then,” she continued, “it could be used to give someone a diagnosis?”

“Yeah.”

She nodded. An idea occurred to her. As he strolled away she called his name, then said, “I like your new haircut.”

*

They sat down for dinner at Chutneys Bangladeshi Restaurant. Roy wore some kind of cardigan over some kind of shirt. But at least he had made half an effort.

“This is nice,” she said. “I’ve only ever collected Chutneys’ takeaways.”

“Same here,” he replied. “Not cool to go to a restaurant alone.”

She smiled. He was the cute geek type, she decided.

“Do you ever work with the data I gather?” she asked.

“Expect so,” he replied. “But we don’t need to know sources. When you’re designing the English National Virtual Patient, all data is good data.”

She nodded, keeping her gaze firmly locked to his. “When you say it like that, it sounds so imposing.”

He shrugged. “Engineers and electronics guys have been making virtual designs for decades, they’re brilliant for testing and stuff. But with the lack of public funding and the rise of AIs making diagnoses better than doctors, it was inevitable there’d be a race to build things like George.”

“Are we winning?”

“Oh, yeah. Of course!”

She smiled, feeling hopeful. “Really?”

He laughed. “There’s millions of pounds of bonuses depending on it. I’m hoping to buy a flat.”

She glanced away, annoyed at his unthinking acceptance of such corporate ploys. “Do you think the NHS should have George?” she asked.

He snorted. “Don’t you watch the news? The NHS is cracking up. It’ll be snapped up by 2050. I hope Goode gets the decent stuff – the data.” He grinned. “Bringing the bacon home.”

Now she had to act to keep irritation off her face. “But the NHS has been around for almost a century.”

“So? Listen Mel, you need to lighten up. Goode Ltd is a home for people like us who know data. I’m not getting a better job anywhere else… well, not in the foreseeable. They need me right now. I have to balance huge amounts of data to make George racially diverse.” He leaned forward, steepling his hands together. “This is England, you know, and there’s all shades of skin. George is going to be the perfect mix of every race living here. Nobody’s gonna drop any identity politics shit on us.”

“What about different ages?” she asked.

“Built in. George serves for all.”

She smiled, buoyed by his optimism. “You’re a good man, Roy. I like the way you take those things seriously.”

He nodded. “Oh, you’ve got to.”

“And what does it stand for?” she asked.

“What does what?”

“George.”

“Stand for?” he asked.

“Yes – the acronym.”

“He’s just called George. It doesn’t stand for anything.”

Mel sat back. Now she felt like she had with Dr Lee. “Not an acronym?”

“He’s called George after-”

“You mean,” she said, “it’s a male virtual patient?”

“Yeah.”

“But what about women?”

“Well,” he replied, “we had to choose one or the other. Men are kind of like the default, you know? There’ll be adjustments for women, I’m sure.” He sniffed. “Not my department.”

“Then whose department is it?”

His shrug was all the reply she needed.

Mel’s irritation turned to fury. She was in pain, bleeding again, with no answer in sight from any GP. Online sources gave her nine possible diagnoses, including a professional one she paid £599 for, which told her she had erratic, painful periods with likely hormonal variation on top. Tranexamic Acid or the pill would stop the bleeding, apparently.

Dr Lee’s final insult returned to haunt her: once you’ve started having babies…

For the entirety of her employment at Goode Ltd she had assumed George was an acronym: General English blah blah blah blah. It never once occurred to her that they would use a male body to represent everyone in England. Now rage made her tremble. One woman sat in the boardroom of Goode Ltd, while every IT and Data Department manager was a man. Of course, all the cleaners were women, like the assistants in the canteen.

Having previously been agnostic regarding the worth of Goode Ltd, and having pondered the state of private healthcare only in PSHE lessons, she now felt consumed by a desire to do something about the situation she lived with. Every day the papers enjoyed their feeding frenzy around the demise of the NHS in the hands of the new government. Isolated from Europe, separated from Scotland, and with America too busy in China to worry about anything else, England was becoming a backwater: falling apart at the seams. The economy meanwhile was turning to China and Korea in a last effort to stay afloat.

But what could she do for ordinary people? She was a functionary in a faceless corporation.

Of course, there was always Roy and his inside information… He had gone on one date with her, so the possibility of using him remained.

She felt no guilt. This had to be done for over thirty million women, all of whom were supposed to be represented by the male virtual body called George.

#

The return visit to Chutneys was a more polished experience. Roy wore a cardigan and a shirt, and had combed his hair. She, meanwhile, dressed down to meet him half way.

“How shall we do this then?” she asked.

“I could hack into your NHS record.”

“Then feed the data to George?”

He nodded. “Unless you want the private doctor’s-”

“No,” she interrupted. “I want to use only Goode IT. No NHS computers, no private.”

“Why not?” he asked.

Though she knew she must not, she hesitated. Despite the warning she gave herself, she glanced away. Impossible not to. “Well,” she said, cracking a papadum to distract him, “we need to keep this in-house. I know it’s not illegal, but it is unethical.”

He shrugged. “It’s a perk of the job, you know? Even unethical perks aren’t really unethical. It’s like stealing stationery – corporations expect it. So, we take perks all the time.”

She looked at him. “We?”

“Us lads. It’s data, isn’t it? Be mad not to use it.”

“You mean, you use it for your own purposes?”

He nodded.

“But doesn’t that breach the data protection–”

He waved a hand to stop her speaking. “Yes, it does technically, but we’re not in Europe any more, are we? GDPR was their idea. And this country is going to the dogs, Mel. If you’ve got any sense you’ll do the same thing before this company is bought by the Koreans. In a decade we’ll be out on our ears.”

She had never pondered this. “You’re serious?”

“Enjoy the ride while you can. Accumulate. Get those perks, even if you believe they’re dodgy. Chances are they’re not anyway. And if nobody finds out, they’re definitely not dodgy.”

Mel nodded, though without enthusiasm. Was this the way of things in her future? Dog eat dog and everyone for themselves? That was not a world she wanted to be part of.

She snapped another papadum, not knowing what next to say.

“Listen,” he said, “I totally get it that you’re frustrated by doctors not giving you a proper diagnosis. My Mum had PCOS, misdiagnosed for ages. But I’ll help you. If you really want to do it in-house, I’ll make some virtual servers and we’ll use them.”

Mel stared at him, then took a sip of her water. She knew what a virtual server was. “You mean, George’ll fit?”

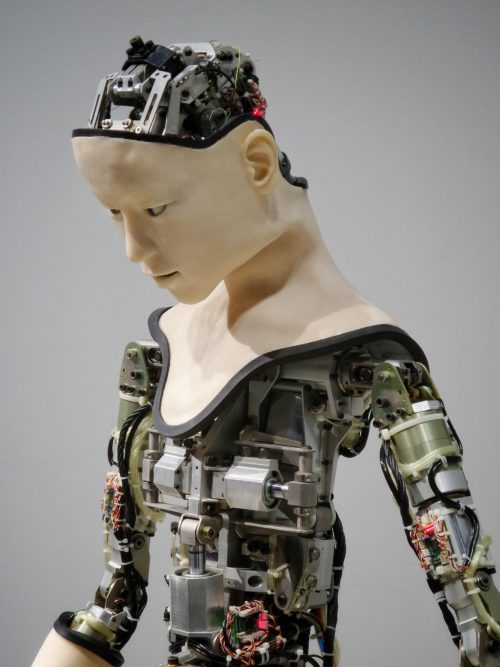

“Sure! We do use Korean mainframes, you know? George doesn’t need all the data to keep him going, that’s just what we use to train him up. Hence, you and the Data Gathering Department. The AI itself though… that’s the special thing.”

“But, then couldn’t George be stolen?”

“Not from Goode! Our protection is A-grade Chinese. But, like you said, if we’re only pushing a copy of George onto our own virtual servers, using him to diagnose you, then deleting him, what does it matter? You’re an employee, aren’t you? Perk of the job. Use it.”

She nodded. “Maybe I should…”

He smiled, raising his arms to put both hands behind his head. “Told you I’d help.”

She looked at him. This was the time for maximum flattery. “You’re a good man, Roy. I won’t forget this.”

He sat back, grinning. “I’m good at Goode. You know it.”

There being no other option, they agreed to make the push soon, in the small hours one morning. Some of the senior managers were getting itchy palms about George not being ready on schedule. Hundreds of millions of pounds of profit lay at risk. Shareholders might revolt. The usual story.

Roy took a couple of days’ personal leave so that he needed to catch up extra hours, making an ad hoc arrangement with his line manager to work overnight for a week. This was uncommon, but nothing worth examining by HR. Roy told Mel some employees would be doing overtime as the NHS imploded and Goode Ltd rose from its ashes.

“You mean, feed from its ashes,” Mel remarked, making a fair impression of a grin.

Roy laughed. “It’s the way of the world.”

Standing behind him, Mel nodded. Not for much longer, she thought. She handed him another can of beer, watching his stubby fingers tap over keys. On her mobile, out of view, she videoed him as he typed his passwords.

Roy gestured her to his side. He belched. “Ready?”

Via her phone Mel activated the VPN she had prepared. “Yes.”

“Good. Have a think on your symptoms, most serious first, then all the rest in decreasing order, which we’ll tell George. I’m off for a wee.” He laughed. “B.R.B.”

She grinned at him, then winked. He was full of beer, as she had planned.

While he was away she made the link then gave George a push.

Then she sent an email to a hotshot London journalist: young, hungry. The email would be followed up, she knew.

#

The new community hospital was set in leafy grounds on the edge of town. The waiting room was quiet, Radio 2 playing in the background, with a large area for children; plenty of toys. She was one of eight patients, all women, most of the others each with a child. The receptionist was polite and relaxed. The whole place felt calm.

She smiled. Dr Hobbs was a woman.

The appointment was limited to twenty minutes. Halfway through, Dr Hobbs said, “Have you ever been diagnosed with endometriosis?”

Mel shrugged. “That was one diagnosis, but I never could get anybody to follow it up. They were too busy fobbing me off so they could reduce their backlog.”

Dr Hobbs gave a sad smile. “Things are much better now,” she said. She was clearly trying to be diplomatic – things were still by no means perfect – but the release of George into the open-source community had triggered far-reaching change across the health sector. What had risen from the ashes was not hungry companies like Goode picking over the spoils, but a new NHS, based on teaching and community hospitals and a culture of openness and collaboration…

“Have I definitely got endometriosis?” Mel asked.

“I aim to find out. I suspect you have, but I can’t be certain having met you only once. Of course, I do have access to Georgina, and that will help – AIs can in many circumstances diagnose better than GPs. But you and I will get to know one another, and you won’t be fobbed off by me, whatever route we end up taking to find out what’s causing your pain and bleeding. Of course, if you move house…”

Mel shook her head. “I have a feeling I’ll be staying local for a while.”