latest

Fictions: Life’s Lottery

Life's Lottery

Read the third instalment in our Fictions Series.

Text by Keith Brooke, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

Read the associated “Getting Real” blog, exploring the technology, science, policy, and societal implications of the themes from the story here.

Life’s Lottery

Keith Brooke

Janie checks her stats several times a day. Steps, blood pressure, heart rate, cholesterol, blood glucose… And since the diagnosis, red blood cell count, levels of urea, phosphates and potassium, and numerous other things whose names never stuck in her brain for more than a few seconds.

Now she sits in the scuffed leather recliner, turned to face the window. She likes watching the birds at the feeders when she comes for treatment. The antics of the sparrows and starlings, and the way they suddenly disperse when one of the bigger bullies, a magpie or a squirrel, muscles in.

She gets bored easily, though, and now she taps the Trace bracelet and the window’s glass phases to a newsfeed, personalised with all her social media favourites.

“Hey, Janie, how’s your ranking?” That was Lloyd sitting at the next window, cute as a button and sadly gay as a gay thing.

Janie taps her Trace again, and her stats scroll over the viewing area on her window.

She can’t bring herself to answer, and it’s Lloyd who finally speaks again. “Not so good, huh?”

“Not so good.”

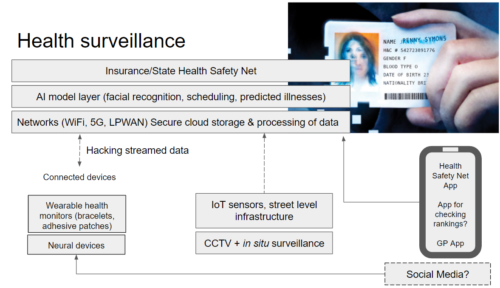

Janie’s ranking is a ballpark figure that tells her how long she has to wait for the op, but there are all kinds of complex processes that go into reducing the weighting of elements such as need, risk factors, resources and so on into that single ranking. There’s also the benefit to society metric that weights the ranking in favour of those with the most to give back.

There are good days and bad, and sometimes it’s hard for Janie to understand why her ranking fluctuates.

On good days it’s like when the map tells you your journey is going to take three hours and you see that estimate steadily reducing until you make it in two hours fifty. It’s trivial, but being that fraction ahead of the projections makes you feel so good.

Other times, your ranking can plummet over the course of a day. An outbreak of respiratory disease at the other end of the country can have knock-on effects on queues throughout the National Health Safety Net. A swing in the markets can dramatically nudge the algorithms that determine supplies of operating theatres and staff resources.

Having so little control messes with Janie’s head. Sometimes her thoughts turn dark, and it’s as if someone has dimmed the world’s lights.

Sometimes she finds herself considering all the ways she could end it all.

Then she catches herself wondering… Just what can her Trace pick up on? And even if the device can’t read your actual mind, it can certainly pick up on the physiological response to your mental state. Does simply thinking dark thoughts somehow feed into Janie’s ranking metrics? By contemplating ending it all, has she reduced her potential benefit to society, and so nudged her place in the queue even lower? The world hardly needs to be nursing another depressive on the rollercoaster of life.

Paranoid, she knows. But as they say, that doesn’t mean…

Her thoughts are interrupted. A call from her mother.

She okays it, and the familiar features pop up on the window before her.

“Hey.”

“Hey, Janie. How’s things?”

“Things are good.” She even manages a smile. “Everything’s fine. Not long at all before my op, according to my rankings.”

The lie came easily, as it always does.

*

Next time she emerges from the clinic, Janie spots Lloyd in the park over the road, smoking a roll-up.

“Hey,” she says, joining him on the grass. And then she realises it’s not just a cig, but a joint.

There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. It’s a free world.

But the Trace always knows, and it would feed such anti-health behaviour into the stats. A shared joint or a couple of beers would be flagged as a big fat I Don’t Care and your ranking for suitability to receive care would plummet.

“Seriously, dude?” she says to Lloyd, eyebrows raised in what’s meant to be a hard stare.

He only giggles in response.

“What about your metrics?”

Now he shrugs.

When he offers her a puff, she declines.

“Come on, Jay,” he says to her. “Surely you cheat your Trace sometimes? How do you get by without the occasional spliff?”

She doesn’t answer. She didn’t even know you could cheat the Trace. Is there a way around the constant monitoring?

Sometime later, she says, tentatively, “So… How do you…?”

She sees in his eyes that he understands. She’s never done this before. Never cheated the system.

“There’s a hack,” he tells her with a lazy, stoned grin. “There’s always a hack.”

*

What is it they used to drum into you at school? There’s no such thing as a good drug. Even the most harmless illicit substance could act as a gateway drug to something more heavy.

That’s what it’s like. Not the handful of joints Janie has smoked since Lloyd shared the hack, or the moodies he’s passed on to her.

The hack itself is the gateway drug for her. Because once you’ve cheated the Trace once, then why not do it again? Why not look for other hacks?

Sitting in their room at the clinic, with its flowery wallpaper and the picture windows overlooking the bird feeders, Janie glances across at Lloyd. He looks chilled, and now she knows why he finds it so easy to relax.

“Hey, Lloyd.”

“What’s up?”

“My ranking. It’s going nowhere.” For weeks now her ranking has been fluctuating at around the same level; she’s making no progress towards the op.

“They like it that way, don’t they? There’s more money for the med firms in long-term care than in fixing us, isn’t there?”

Lloyd has just said out loud what has been nagging at the back of Janie’s mind, that there is no way out of this for someone like her. Worse, because if the financial metrics in the system change so that the Safety Net can no longer support this kind of care, then what will become of her?

“So,” she says to Lloyd. “This hack…” The hack works by modifying the data her Trace sends back to the system, checking for warning flags and altering them before they’re recorded. An algorithm riding on the back of all the other algorithms.

“Huh?” He seems thrown by the change of tack.

“If it can filter out the illicit substance metrics, then… are there other hacks, too?”

He smiles now. “There’s always a hack,” he tells her.

*

“Hey, Mum.”

“Hey, Janie. How’s things?”

“Things are good. Everything’s fine. Not long at all before my op, according to my rankings.”

This time the smile is spontaneous, genuine. This time she doesn’t even have to lie. She’s never had a ranking so high, and although she still gets days when inexplicable fluctuations bump her back down a little, it’s definitely a case of two or three steps forward for every step back.

It feels like a game, watching the numbers. Seeing all the smileys and thumbs up.

She isn’t getting better, of course. She knows that.

But she’s getting closer to her goal, which is what matters.

Lloyd had set her up with a friend who hacked into her profile. Now, as well as the meta-algorithms that filter out records of the occasional joint or mood enhancer, there are others that tell the system she’s becoming more unwell, that her treatments aren’t working.

“How long?”

“I don’t know. Months still. It varies. But that’s better than years.”

And even if that goal still isn’t quite within reach, it’s nice to at least feel you’re making more progress than not.

*

“There’s always a hack. Another hack.”

Sitting with Lloyd on the grass in the sun. That smile on his face. Fancying the gay guy pretty much sums up Janie’s life, but she doesn’t dwell on that now. She’s intrigued by what he’s saying and by the look in his eye.

“Your profile is skewed,” he tells her. “Like it’s calcified by your medical history. A few hacks can give you a boost and make you feel better about your place in the world, but they’re never going to be enough.”

“But how do you change that? I can hardly change who I am.”

“Oh but you can.” That smile again. “A fresh start, Janie. A clean slate. People like us don’t stand a chance. Either you’re happy with the status quo, like me, or you need to become somebody else.”

“Identity theft, you mean? I can’t steal someone else’s identity. Someone near the top of the rankings… they need to be there. I can’t steal their chance at treatment.”

“Not theft. Not somebody else. A new identity. One customised to play well with all the algorithms. I know someone who does this kind of thing. Takes who you are and what your needs are and extrapolates them to a time when everything has got worse and you’re at the top of the rankings. It’s an alternative version of you, only when things are much worse. You’re not jumping everyone else’s queue; you’re jumping your own queue.”

She knows he’s talking double-speak. Knows that however you dress it up, you’re bumping someone else back.

And sometimes it’s so easy just to let him do that.

*

The jump in rankings wasn’t dramatic at first. Lloyd had warned her about that. A sudden spike would always look suspicious.

But now… Seeing the smileys and thumbs up, the ranking changing from red to amber…

“Weeks, not months, Mum, that’s what they say. It’s looking good.”

Lloyd hadn’t warned her about the plateau, though. Hadn’t told her that once you hit a certain level in the battle for resources there are so many conflicting demands that you need something really special to achieve that final push.

One step forward, one back again. The good days balanced by the bad. It’s all an illusion, cast over a system that works by trapping people like Janie and Lloyd into long-term management of conditions rather than cure. An illusion that dangles hope, only to snatch it away again.

Now, she finds those dark thoughts creeping back in, and the paranoia that her mood will feed those backward steps, make things worse again.

Now she hates the treatment sessions, gets annoyed at the freedom of the birds and squirrels beyond the window. Doesn’t even answer her mother’s calls because she can no longer force the smile and the lie.

Hope is a commodity hard won and easily lost.

*

“Penny Symons?”

It takes Janie several seconds to remember that’s the name used on her fake identity. The face on her home screen is anonymous, probably an avatar.

“It’s about your Trace ranking, Penny.”

Janie stares, her heart suddenly racing. She hasn’t missed the irony that her Trace would detect the physiological response, and no doubt confirm her guilt before even a word has been spoken.

But then the caller goes on. “I’m calling from the Real Network. I work on a new show called Life’s Lottery. We’d like to invite you to take part.”

“I’m sorry,” says Janie carefully. “I don’t understand.” Real Network puts out all kinds of reality TV shows and games. Janie is hardly bikini-wearing love-interest material.

“Our ’bots have been monitoring the rankings for patients whose rankings look promising. Steady rises, indicating viability for resource-restricted operations, but who are never likely to rise high enough to qualify for an operation on the Safety Net.”

The part that catches Janie’s attention is the confirmation that, no matter how close she gets, she’s never actually going to get her operation.

“I don’t understand.”

“We’re offering you a chance at the treatment you so dearly need, Penny. Take part in our show and you have that opportunity.”

A chance at the operation she dreams of.

And then she realises: not Janie, but Penny. If she goes along with this, she’ll have to do it as Penny Symons. Maintaining a fake ID and Trace profile has been easy, but can she really hope to pull it off in real life?

She swallows. “Okay,” she says. “I’ll do it.” Only in that instant does she realise quite how desperate she is.

*

The show is going to start off with sixty-four contestants. Janie knows it’s quite amazing she’s somehow been selected and reached this far, but also her heart sinks because that’s a big number and only four winners will get the treatment they need. The rest will just go back onto the queue again.

She’s already spent a week being coached about how to present herself on screen. Being groomed by make-up artists and stylists. Enduring hours of grilling about her personal and medical history where at any moment she risks being exposed as a fake.

Somehow, she’s still here. Winging it. Scraping through.

She’s so close. She can’t lose this opportunity now.

She finds herself sitting in an interview room, exhausted after another prep session. The cameras are off now, the harsh studio lights powered down and her eyes adjusting to more normal levels of light. They record these sessions so she can see how she comes across, part of the grooming process. Training her for the show.

Now, though, it’s just her and one of the show’s researchers – Camilla or Arabella or something.

“Penny, we need to be frank. We need to talk to you about your identity.”

Now Janie is quite used to being addressed as Penny and not her real name. Maybe after all this is over she’ll stick with it, a real fresh start.

We need to talk to you about your identity.

It takes a second or two for the words to sink in, and then she’s hit with a rush of that familiar fear: they’ve uncovered her deception. They’re going to kick her out. And worse: what will happen to her in the real world: an identity thief, a Trace cheat. Does the Safety Net still cover people like her?

“…it’s like the tigers.”

She hasn’t listened to the first part of what the researcher said. “Sorry?”

“Think of the big conservation charities, Penny. It’s all about the glamour. It’s easy for them to raise money to save the tigers and the exotic birds. But what about all the other less appealing creatures? Let’s face it, Penny: you’re no tiger. Your condition isn’t rare. Your stats are alarming, but look at you: no viewer is going to believe you’re at death’s door. You’re not a key worker, you don’t have a heart-rending family history to pull in the viewer votes… You’re never going to win a show like Life’s Lottery. Your profile simply isn’t dramatic enough.”

“What are you telling me? Are you kicking me off before the show’s even started?”

Then, the smile. “Of course not, Penny. What kind of people do you think we are? No, what we need to do is finesse your presentation. We need to identify all the areas of your profile that don’t score well with the focus groups and tweak them. We can edit your benefit to society ranking. We can window-dress your personal history, invent a wholesome family and friends who will miss you.”

“You mean… you mean you’re going to give me a fake identity?”

“Not fake. Enhanced. There’s nothing more real than artifice. Nothing more convincing than sincerity, and as they say, if you can fake that…”

Janie stares at the researcher. Struggles to get her head around the multiple levels of fakery and irony.

Then: “Okay. I’ll do it. I’ll do whatever you need. Make me whoever I need to be, as long as I have a chance of being fixed.”

The smile again. “Do you think you can carry it off, Penny?”

And now Janie smiles in return, a genuine, spontaneous smile. “Oh yes,” she tells the researcher. “Trust me, I can do this.”

[With thanks to Dave Dawes for sparking this story.]