latest

Fictions: It’s Her Turn

Read the twelfth and final instalment in our Fictions series.

Text by Anne Charnock, artwork by Vincent Chong.

Fictions: Health and Care Re-Imagined presents world-class fiction to inspire debate and new thinking among practitioners and policy-makers. To find out about the project, the authors and to read other stories in the collection, click here.

It’s Her Turn

Anne Charnock

I remind myself that Noah and I are each coping in our own way with Alice’s absence, so I need not feel guilty. For his part, Noah insists that we keep her bedroom door closed. He hates seeing her neat desk, the sure indicator that Alice has moved on. Whereas I love to spend time in her bedroom. In a minor act of subterfuge, I wait for Noah to leave the house and then I slip into her room, lie down on her bed and listen to the playlist. The one I made for her before she was born. The bedroom is chilly because there is little point in heating it while she lives away. But I wonder while listening to the songs—mostly sung by me, a couple by Noah—if I should air the room every Friday in case she springs a weekend visit.

Last night I reminded Noah that he and I were the same age as Alice when we left home. I never cast a backwards glance and I’m damn sure he didn’t either.

“Keep a brave face, for her sake,” I said. “It’s her turn. She needs to make new friends, start new adventures like we did. And one day she’ll have her own stories to tell—adventures and mishaps.” He glared at me. “Yes, Noah, mishaps and funny stories to tell her friends and maybe her own children.”

Over breakfast this morning, Noah blurted: “It’s two months today.”

I took a bite of my toast, noticed his slumped posture and wondered if he would feel better, more positive, if he stiffened his spine. I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand, and threw him a quizzical look as though I could not follow his meaning.

“Alice!” he said.

I reached across and took his hand. “Alice will open up our world. Wait and see! She’ll bring her friends home and draw us into her new life, wherever she ends up and whatever she ends up doing.” His head sank, chin to chest, but I persisted. “We’ll be part of that new world with her. She will not leave us behind.”

*

Mixed memories, listening to the playlist after all these years. Those high notes I can’t quite reach make me shake with silent laughter and I see myself placing my hand on the baby bag, feeling her weight against my palm. And I recall the opening ceremony. The doctors called it the birth, but to my mind you can’t refer to the opening of a bag—unzip!—as a birth. For me, I think of my preemptive caesarean at twenty-two weeks as the birth, and the rest of her gestation in the hospital ward as a limbo. It felt like a punishment aimed at me, for getting pregnant at the ripe old age of forty-five.

For the opening ceremony, I wore a new lightweight dressing gown with plain, sensible knickers underneath. The midwife unzipped the bag and lifted Alice out. I had asked if I could lift her out but, for insurance reasons, that was forbidden. They did not trust me. I lay back on the gurney and the midwife laid Alice on my naked chest. Overwhelmed, I told the midwife, and the doctor who had dropped in, to stand away. I remember murmuring, I’ve got you back, Alice. As though she’d been held hostage.

I won’t tell Noah I’ve been doing this—listening to the songs while lying on her bed. I like to curl up in a foetal position and I know this would freak him out. I’m completing the circle, it seems; she and I have switched positions.

Noah and I rarely talk about my early dark days after the birth. Early dark years, in fact. And though we have wonderful memories of Alice growing up, learning to walk, learning to speak full sentences, there is always the memory of my anxieties. It goes unspoken that we made a mistake when we agreed to remote gestation for her sake, not mine. The separation anxiety I experienced when we left Alice in the gestation ward, the continuing anxieties I felt when we brought her home. I hated her being out of my sight. I bet it’s a newly classified phobia. Maternal separation anxiety as a result of pre-term foetal migration and gestation. Or some such.

I came through all that, thanks to the therapy.

In the weeks before Alice left home, I felt confident I could navigate this new adult form of separation. In the event, her departure felled me for two weeks at least. I felt the old pain of separation like a muscle-memory. Constantly lightheaded, reeling as much as Noah at that point, I found it unbearable to see photographs of her around the house. I said to him, “You’d think it would help seeing pictures of Alice around the house, but it feels exactly the opposite.”

He agreed. We collected all the framed photographs and placed them inside the living room sideboard. A few days later my palpitations eased and the dizziness stopped. Looking back, I think it helped that Noah needed my support, because this pain of separation was, in truth, a new experience for him. Whereas I knew the pain would pass, eventually. I had lived through it once and I would do so again.

*

I lie on her bed and listen to my song about blue skies. I sang it for Alice before she knew anything about the world, my playlist being fed to her as she swam, or at least wriggled, in her artificial amniotic sea. And we chose this particular song to play while the midwife lifted her from the bag. I reckon Noah is the one who needs blue skies, needs to escape this house, this upstairs landing, the closed bedroom door.

*

We make a picnic together at the kitchen island, and I notice Noah placing three enamel cups in the rucksack instead of two. I don’t say anything. He will realise his mistake. Sure enough, he stalls and then removes one cup. I look away and cut two slices of cake.

“The fresh air will do us good, Noah. I think we need to get out more and go to new places like we’re doing today. We need new adventures, ourselves.” I want to avoid trips to favourite haunts because our memories of those places are too tied up with Alice. “You know, we could book an empty-nest therapy session. But maybe we should hold off until we’ve renewed the health policy. The premium might go up if they think we have ongoing issues.”

“Yeah, let’s wait.”

I’m not sure he is paying close attention, so I press the point. “You know, I’d be happy for you to book a private session if you feel you need it.”

“Let’s see.” He fills the flask with black coffee. “I keep seeing her at the college campus—waving us away. You and me in the car park. She’s waving down to us from her tiny room. I mean, how can you look after a child for all these years and simply drop her off? Wave goodbye.”

“It’s just the way of the world. They strike out.”

Friends have told us not to worry. That once Alice has visited home two or three times, we will understand that the separation isn’t terminal. They know this because they’ve been through it themselves.

*

We set out for the coast, for the nature reserve near Dungeness, but before we reach the end of our street we turn back because we have left the binoculars at home. Then a second false start when I realise the flask of coffee is still sat on the kitchen island. We laugh at ourselves as we set off for a third time, and I sense this could be a silly, fun day. Yes, we need to stay silly.

On the journey we talk over our holiday plans for the next year or two. Noah says, “I bet if I told Alice we were planning a week in New York, she’d be desperate to come with us.”

“True. But I thought we’d decided against air flights.” I kicked myself for nit-picking. “She really likes train journeys, Noah. Let’s float the idea of taking a train to Paris and then onto Moscow. She’d be hopping mad if we went without her.”

Noah is smiling.

*

“We should do this more often,” he says. We sit at a picnic bench on the edge of marshland—a quick snack of coffee and cake before heading off on the nature trail. He sits with his elbows on the table and the binoculars held to his eyes. “Bearded reedling,” he says. “Male. It’s ringed on its right leg.”

“Oh! Tell me its journey.”

“Spotted at Lodmoor and Brading Marshes.”

He passes me the binoculars and I search the sky.

“We haven’t used these binoculars much, have we? We don’t have a badge for fifty sightings yet. Thirty-eight so far, it says. Let’s try to nail it today.” I train the binoculars on the nearby long grasses. “Oh look! A female bearded reedling. That counts as an extra sighting even though it’s the same species.” I capture an image.

Noah stands up and packs up the flask. “It’s a real tonic getting away from town. Much better than a stroll around the park, surrounded by other people.”

“Just takes a bit of forethought. We need to plan our weekends. Get out into the countryside. And, we don’t have to fit around Alice’s plans any longer.”

“She never expected us to fit around her,” he says. Noah has always leapt to her defence even if no criticism was intended.

“I know, but we did fit around her. Not that I ever minded.” I pass the binoculars back to Noah. “Come on, let’s win the badge. Eleven to go.”

*

An hour passes and we find ourselves within one sighting of our goal. So far most of the birds we have spotted are small creatures that flit through the marshland grasses. I plan to study our captured images when we return home so that I might, one day, recognise the birds without the prompts.

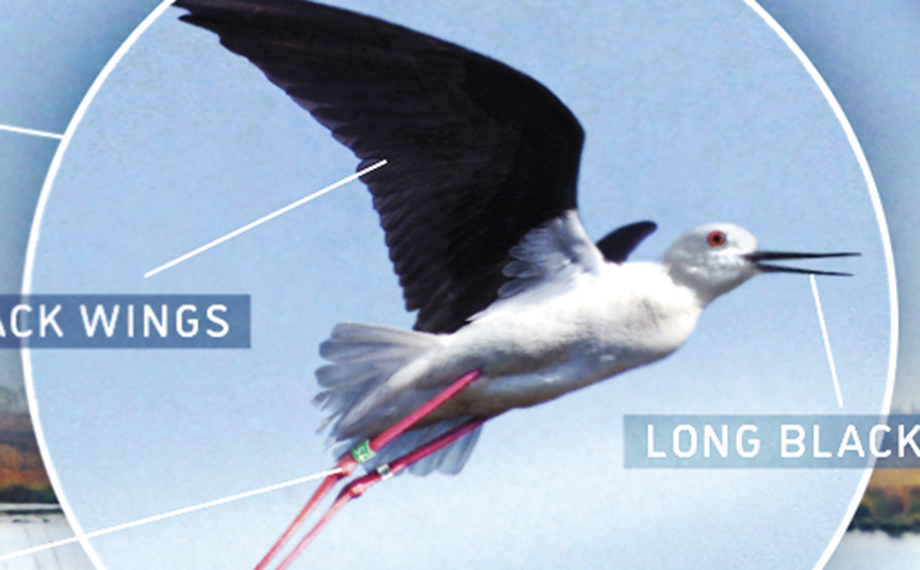

“What’s that? A heron? Look at the long legs,” says Noah, pointing into the sky.

“Can’t be. Herons have bigger bodies. Oh wait, there’s a whole flock of them!”

He raises the binoculars and reads the ID info aloud. “Black-legged stilt. Brilliant. Our fiftieth species.”

He turns and gives me a high-five. I’m pleased Noah spotted them. They seem so calm as they glide rather than fly, their long, pink legs trailing. But their cries sound rusty, inelegant. I laugh. “Is it me, or do they sound like bath toys, those squeaky rubber ducks?” The stilts circle and settle out of sight in the marshland. “What’s the read-out?” I ask.

“One of the stilts is ringed. Last spotted at Cliffe Pools in Kent.” He fiddles with the buttons. “I’ve sent the image to Alice.”

A few minutes later I receive a message from her. Glad you are out and about. Then two minutes later. Are you home next weekend? In need of home cooking!

*

On the way home, super relaxed after the fresh air—three hours having flown by—I suggest we take up birdwatching as a shared hobby—for the pure pleasure of it—and attempt to learn a few of the bird songs.

Noah is nodding, but I can tell his thoughts are elsewhere.

We travel in silence for ten minutes or so when he says, “Is this how it felt for you after Alice was born? You know, all the therapy you needed?”

Tears well up, and I swallow. I turn to him without speaking, and he says, “I’ve only really understood during the past few weeks how you must have felt. I grasp it now. How you wanted Alice within reach all the time. I’m going through that now. My chest is hurting all the time and I keep thinking—where is she? Is she in danger? Does she even see the danger?”

“It will ease up, believe me.”

As we turn into our street, I say, “I think we should visit Cliffe Pools next. Follow the stilts’ migration route, see their other habitats. We should splash out and buy a second pair of binoculars.”

“Cheaper than private therapy,” he says.